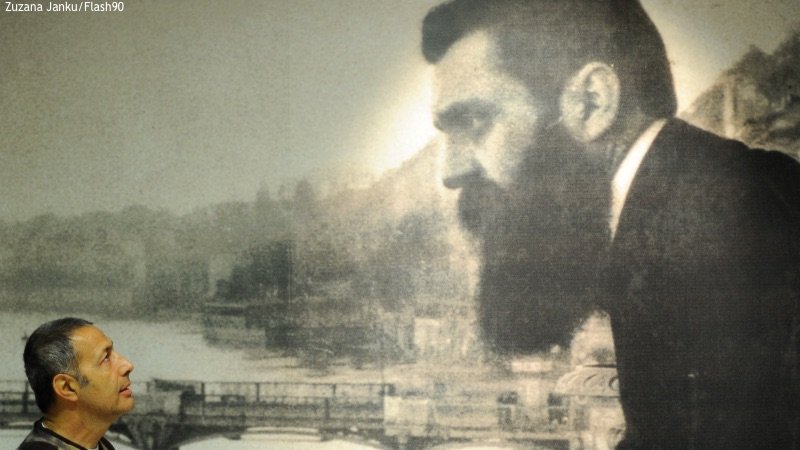

Theodor Herzl, who turned the Zionist vision into reality, died 114 years ago, on July 3, 1904. He was only 44, and his untimely death sent waves of anguish throughout the Jewish world. Obituary postcards spoke of him as “Messiah,” and Jews of all shades lamented his sudden departure.

This, of course, doesn’t mean that he was free of criticism, but since no human being is spotless, one is left with deciding whether to dwell on the insipid, or the gist. If one were to choose one thing from the insipid, then what has tarnished Herzl’s reputation more than anything else was his youthful thought of converting the Jewish people to Christianity as a way to escape the harsh reality Jews were facing. In 1892, Herzl wrote to Moritz Benedict, the editor of the influential newspaper Neue Freie Presse, that once hostility toward the Jews subsides, “Jews, as a whole, should convert to Christianity.”

In an article that appeared in 2004, on the 100th anniversary of Herzl’s death, seasoned journalist Ariana Melamed reminded her readers of this “sin,” along with other trivial mischiefs, in hope of further corroding the image of Herzl, and Zionism. Anti-Zionist Orthodox Jews are doing the same, with the same zeal and goal in mind. What both camps fail to mention is that Herzl mentioned this idea before he got into politics and the Zionist movement in 1885, and that in fact he never seriously contemplated such an idea.

In a 1985 note to his diary, Herzl addressed the topic of mass conversion. “These were vague declensions reflecting youth’s weakness. I say to myself with all honesty … I have never seriously considered to convert.” Herzl’s monumental achievement confirms every bit of his rejection of the notion of conversion.

Melamed and other like-minded secular Jews are highlighting Herzl’s [lack of] morality [like his venereal disease], in a further attempt to slaughter Zionism’s most sacred cow. Against this unfortunate trend rise an increasing number of religious Zionists who are trying to paint Herzl as a leader almost on par with Moses. The most difficult thing to explain to any religious person is why the modern State of Israel came into being through the work of a secular redeemer.

At a humble memorial service held on July 3, Rabbi Uri Sherki offered a compelling explanation that views Moses as a secular redeemer, as well. Sherki accepts the explanation of Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin (Natziv of Volozhin 1816-1893), who was probably the first to address the problem of “secular redemption.”

According to Berlin, Moses was punished because he thought the people of Israel would not accept him due to his appearance and speech being that of an Egyptian. Moses doubted God’s choosing a secular Jew, himself, to bring Israel out of Egypt. This is expressed in Exodus 4: “But behold, they will not believe me or listen to my voice, for they will say, ‘The LORD did not appear to you.'”

Then, as today, people find it difficult to believe that God can speak and work through secular Jews. The convention dictated that Aaron, not Moses, was the natural candidate for leadership, since he wasn’t steeped in Egyptian culture, like Moses was. Moses, accordingly, was punished for assuming that a secular redeemer is inconceivable. He doubted God’s wisdom and limited the scope of his actions.

Doubting Herzl’s achievement just because he didn’t wear a kipa, leading Zionist rabbis now acknowledge, is as severe as doubting Moses.