(JNS) For the first time anywhere in the world, desalinated seawater is being pumped into a natural freshwater lake. Israel’s new “Reverse Carrier” project, designed to refill the Sea of Galilee (Kinneret), is a global first. “Instead of taking the water from north to south, we’re taking it from south to north and reversing the flow back to the Sea of Galilee,” Lior Gutman, spokesperson for the national water company Mekorot, told Israel Innovation News.

Built in the 1960s, the National Water Carrier once delivered water from the Galilee southward to the Negev, sustaining farms and cities through decades of scarcity. Now, a similar network is running in reverse, pushing surplus desalinated water north toward the lake, mainly in winter months when domestic and agricultural demand is low. The project, valued at nearly one billion shekels ($302.8 million), represents a striking shift: from a system built to draw from the lake to one built to sustain it.

Israelis walk where water used to be, due to a winter with very low rainfall, Kibbutz Ginosar, Sea of Galilee, Oct. 4, 2025. Photo by Michael Giladi/Flash90.

Only a generation ago, the Kinneret was a source of national anxiety. The lake’s depth was measured obsessively against red-line markers that warned of ecological collapse. The upper red line meant danger; the lower one forbade pumping altogether; beneath it lay the “black line,” a threshold beyond which permanent damage loomed.

For decades, the Kinneret served as the only source of water for many Israeli households. But repeated droughts and overuse left the shoreline retreating and the public alarmed. Campaigns like “Israel is drying up,” a nationwide public awareness initiative to convince the public to dramatically reduce domestic water consumption, became part of everyday life. “We dropped below the lower red line and came close to the black line,” recalled Firas Talhami, head of the Water Authority’s northern region, in a recent interview with Ynet.

Israel’s transformation from scarcity to surplus began in 2005 with large-scale desalination along the Mediterranean coast. The new plants freed the country from dependence on rainfall and made it effectively water-secure. As a result, the Kinneret’s level stopped dictating national policy.

“Israel is a completely different place in terms of water security compared to 20 years ago. Our desalination system has created a new reality where Israel is figuring out what to do with the water surplus rather than worrying about conserving water,” a spokesperson for the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure told JNS. “Of course, we can’t be too comfortable. We always need to continue innovating and inventing newer and better solutions in water technology, but for now, the situation is stable,” he added.

The Sea of Galilee, Oct. 1, 2025. Photo by Michael Giladi/Flash90.

Still, the memory of the 2000s water crisis shaped policy. The 2013–2018 drought, the most severe in decades, rekindled fears of irreversible decline in the Kinneret’s water level and pushed planners to act. “That’s when experts proposed reversing the National Water Carrier and channeling desalinated water into the lake. Ultimately, this became the chosen solution,” Talhami explained.

After several rainy years slowed implementation, the system reached full-scale operation in 2022. Israel Water Authority Director General Yechezkel Lifshitz told The Press Service of Israel that although the system had been functional since mid-2023, “full-scale pumping began only now because of the severe drought. The past winter was the driest in the last hundred years, and the Kinneret dropped to a level we are not willing to cross.”

Israel’s Sorek Desalination Plant, Nov. 22, 2018. Photo by Isaac Harari/Flash90.

While Israel’s desalination network has largely ended the threat of water scarcity, the decision to refill the Kinneret is driven by deeper strategic, ecological and cultural considerations. According to Mekorot, the goal is to maintain the lake’s ecological balance and preserve it as a strategic national resource. Future extensions of the system are already being planned to expand the water supply to the northern region.

The Kinneret today functions primarily as Israel’s emergency water reservoir. Despite the abundance created by desalination, officials stress that the lake remains central to national resilience. “We still consider it as our national emergency water reservoir,” Gutman explained. “Meaning if there’s an earthquake, a continuous state of emergency, or a war, and something happens, God forbid, to the desalination plants, we can and we will use the Sea of Galilee as our main water source for both domestic and agricultural use,” he added.

A view of the Sea of Galilee from the southern Golan Heights, July 12, 2025. Photo by Michael Giladi/Flash90.

Lifshitz echoed this view, calling the Kinneret both a strategic and emotional anchor for the country. “Israel does not have many natural water sources, so this lake is of tremendous importance, both emotionally and strategically. Historically, it has been a vital source of drinking water, and even today it remains a strategic national water reserve,” he explained.

Beyond its functional role, the Kinneret holds deep cultural meaning. It is a centerpiece of Israel’s landscape and a magnet for visitors, especially Christian pilgrims, who associate it with the Gospel account of Jesus walking on water. For local communities, the lake’s health also has tangible economic implications. “The lake is losing a centimeter of water a day in these dry summer months due to natural evaporation,” said Greenbaum, chairman of the Kinneret Cities Association. “We are eagerly awaiting the inflow and hope that with desalinated water we can guarantee a high lake level for Israelis and tourists alike.”

Sea of Galilee, Oct. 4, 2025. Photo by Michael Giladi/Flash90.

Environmental considerations are equally central. Talhami explained that the project will have a profound environmental effect. “We also considered the ecological impact,” he said. “The project will restore the Zalmon stream as a perennial waterway, reviving plant and animal life,” he added.

Desalinated water has different salinity, pH and nutrient levels from lake water, all of which can alter delicate ecosystems if unmanaged. However, Lifshitz emphasized that Israel’s desalinated water is of higher quality than the lake’s natural inflows, with no expected environmental harm.

Israelis enjoy the Majrase Nature Reserve near the Sea of Galilee, northern Israel, July 26, 2025. Photo by Michael Giladi/Flash90.

Experts added that the long-term rationale for the project reaches beyond present challenges. “This project was conceived with a long-term perspective,” said Lifshitz. “We anticipate a decline in rainfall across the Middle East, particularly in northern Israel. Therefore, it is essential to maintain a high water level in the Kinneret to preserve it both as a natural asset and as a strategic national reservoir. Israel’s water sector plans decades ahead; we already have a master plan extending to the year 2075.”

Behind the policy headlines and political symbolism, the Reverse Carrier project is a major feat of engineering, an infrastructure system unlike any in the region. At the heart of the system lies a newly built chain of underground pipelines, pumping stations and local reservoirs designed to allow water to flow back into the Kinneret at the push of a button. “The reverse carrier is a project of serious engineering complexity that demonstrates the quality of Israel’s water tech. Thousands of people and years of work went into putting it together,” a spokesperson for the Water Authority told JNS.

The desalinated water begins its journey in Ashdod, Hadera and other coastal plants, traveling roughly 60 to 90 miles across Israel. Along the way, upgraded pumping stations lift the water hundreds of meters toward the Galilee, while new reservoirs stabilize pressure and flow. At the end of its route, the water surfaces at Nahal Tzalmon.

During peak season, the Water Authority can pump up to 5,000 cubic meters of water per hour, equivalent to 1.3 million gallons. Once additional infrastructure is added, that capacity will triple to 15,000 cubic meters per hour, ensuring a steady inflow even under prolonged drought conditions.

Delivering such volumes over such distances is no small task. Engineers describe the Reverse Carrier as a “pipeline superhighway,” requiring reinforced pumping stations, advanced flow-control systems and continuous monitoring to balance the energy costs of moving desalinated water inland. Desalination remains an energy-intensive process, and in the past, the idea of using it to refill a natural lake was dismissed as prohibitively expensive. Yet Israel’s growing capacity and falling desalination costs have made it feasible.

“During the winter months, the flow is increased, and afterwards it drops to about 1,000 liters per second,” Lifshitz explained, adding that pumping can be reduced or paused during heavy rainfall. The system’s flexibility allows Israel to fine-tune inflows based on weather and demand, ensuring that the Kinneret remains neither overfilled nor depleted.

Israel’s leadership in water technologies has become a central element of its regional diplomacy. At the end of 2021, Israel and Jordan signed a water-for-energy deal brokered by the United Arab Emirates. Under the agreement, Jordan will build a large solar power plant to export electricity to Israel, while an Israeli desalination facility will supply freshwater to Jordan.

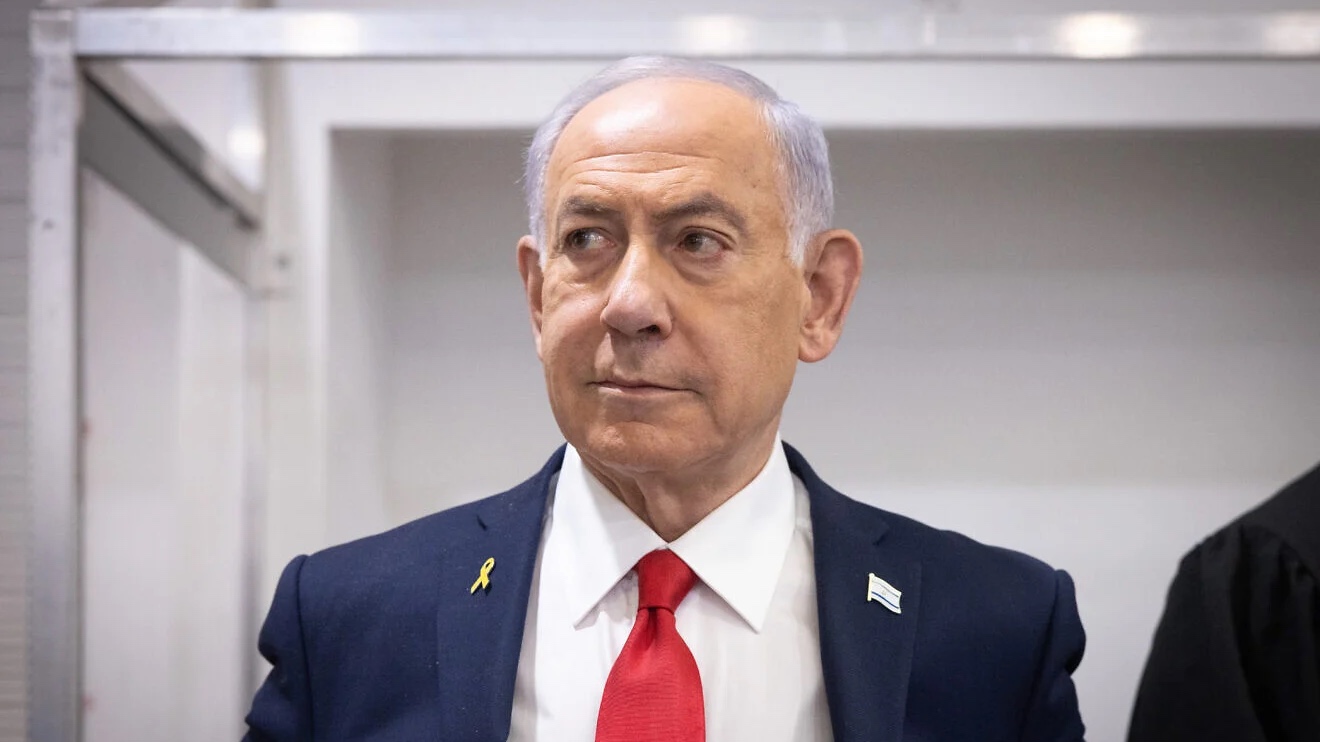

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his Indian counterpart Narendra Modi visit the water desalination plant at Olga beach near Hadera, on July 6, 2017. Photo by Kobi Gideon / GPO.

Israel currently provides water to Jordan and the Palestinian Authority under diplomatic agreements dating back to the 1990s. The 1994 Israel–Jordan peace treaty established a permanent mechanism for annual water transfers from the Kinneret. Even during the severe drought years between 2013 and 2018, Israel maintained its supply commitment. In recent years, Israel has doubled the annual allocation to Jordan from 50 million cubic meters to 100 million.

“In Israel, there are 10 million people, but we provide water for 14 million people. We are in a very good situation in the water sector. We provide water for the people of Israel, we provide water to the Kingdom of Jordan, and we provide water to the Palestinian Authority and to the Gaza Strip,” Gutman explained.

The Kinneret remains a key part of this system. While Israel no longer relies on the lake for domestic consumption, it continues to use it as a conduit for regional supply, sending water from the Galilee basin into Jordan’s network. The next stage of infrastructure will expand this cooperation: a new pipeline is planned to transport desalinated water directly from southern Israel to Jordan. Together with the Kinneret-based transfers, the pipeline will deliver up to 200 million cubic meters annually, about 40% of Jordan’s total needs.

Gutman noted that Israel’s infrastructure and desalination capacity could, in principle, support wider regional assistance. “Theoretically, if the Syrian people or the Lebanese would ask us to get water, we could provide it,” he said.

Israel’s water innovation lies not only in desalination and water networks but in the efficiency and integration of its entire water system. The country has reduced leak losses to only 3%, compared with 20% in the United Kingdom, 50% in Bulgaria and 70% in Romania. This precision management reflects decades of investment in infrastructure maintenance and data monitoring.

Equally important is Israel’s success in water reuse. Ninety percent of its wastewater is purified and reused for agriculture. By comparison, Spain, the next-closest country, reuses only 30% of its water. These two factors, tight loss control and large-scale recycling, have allowed Israel to stabilize its water supply and support continued economic growth even during extended drought years.

Want more news from Israel?

Click Here to sign up for our FREE daily email updates