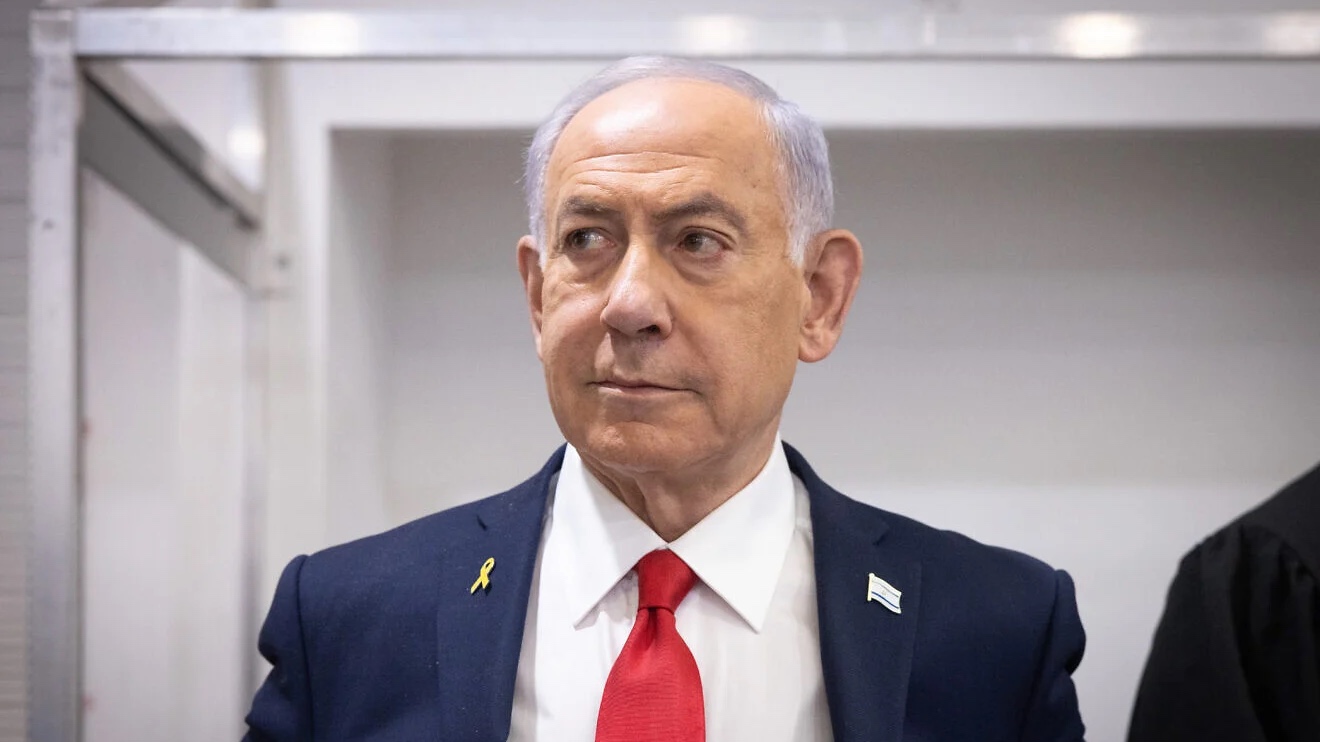

We are just under two months away (November 1) from Israel’s fifth round of elections in four-and-a-half years. The country remains deep in a political impasse making a government lasting more than a year sound like a miracle. Much of the politics related to crisis is still defined around support for or opposition to joining a government led by Benjamin Netanyahu.

It seems as if not a day goes by without political news. Israel’s election seasons are notorious for their unpredictability, the rise and fall of parties and politicians and creative political maneuvering. In Israel, the mantra “it’s not over until it’s over” is an understatement. Here, it’s not over until long after it’s technically over. Israel’s political gymnastics continues to cartwheel its way into the weeks following the final results of the elections in order to form the governing coalition.

Since the dissolution of the Knesset in late June, the political drama has been abundant. All of the parties that hold primaries for their candidates have completed them, thereby formulating most of their candidate lists for the next Knesset. However, the deadline for presenting the final version of their lists is on September 15, leaving plenty of time for the movement of candidates between parties and the merging of parties to form single factions, as well.

Where do Israeli politics currently stand two months away from the election?

Let’s start with the center-left camp

For the first time in its history, the leftist Meretz party held primaries both for its parliamentary candidates and for its chair. The campaign for chair of the party was brutal and personal. The race was set between two candidates—former veteran party leader Zehava Galon and MK Yair Golan. Their visions for the left in Israel could not be more opposite.

Galon, who served as chair of the party from 2012 to 2018, and as an MK from 1999 to 2017, was convinced to come out of retirement and return to politics in a bid to prevent the rise of Yair Golan to chairman. Her views are highly representative of the far-left end of the Zionist spectrum in Israeli politics. She is a fierce opponent of Israel’s presence in Judea and Samaria, serving in the past as the General Secretary of B’tselem, and has called to repeal the Law of Return. Although Meretz has been accused of being a bastion for post-Zionist viewpoints, she claims that the party holds a Zionist view that is tolerant and liberal. Zehava Galon embodies the historical ideals of Meretz.

Yair Golan, in contrast, came to challenge those ideals. Golan is a retired Major General in the IDF who served in several military operations, such as the First Lebanon War (1982), the Second Intifada (2000-2005) and the Second Lebanon War (2006). Although a retired IDF general in a center-left party is hardly news, his position in Meretz is quite unique. Throughout his primary campaign, Golan accused Galon of preserving Meretz’s status as a small party that deals with “esoteric issues.” He even challenged her on Zionism, stirring up public debate about whether or not Meretz is really a Zionist party. Golan’s ideology is hardly different from other party platforms in the center-left camp, such as those of Labor and Yesh Atid. Much of Meretz’s electorate could easily sense this, and thus it was not surprising when Galon defeated him with 60% percent of the vote.

Currently, the biggest challenge for Meretz is ensuring that they finish the race above the electoral threshold. As of now, polls show the party receiving five or six seats, more than what they secured in the previous elections. Furthermore, there is tremendous pressure on Galon to push for a joint list between Meretz and Labor in order to maximize their electoral potential.

In contrast, to the Meretz experience, Labor’s primary for chair of the party could hardly be called a race. Current head of the Labor party and Minister of Transportation, Merav Michaeli, won in a landslide, taking about 80% of the votes. She’s the first head of Labor in quite some time to serve two consecutive terms. However, the party is trending between 5-6 seats in the polls.

Its greatest challenge throughout the next two months is to distinguish itself from Meretz. Like Zehava Galon, Mereav Michaeli is under tremendous pressure to join forces with Meretz. However, unlike Galon, Michaeli has until now outrightly rejected the proposal, claiming that there is little ideological compatibility and that electorally it will decrease the number of seats controlled by the center-left bloc.

Michaeli is correct in her claim that a joint list between them is unlikely produce the desired effect. When both parties ran on one ticket during the election of March 2020, they finished with just seven total seats. Today, they separately can win a total of between 10-11 seats. In order to maximize their electoral potential, they should run on separate tickets.

However, looking at the current list, Michaeli is wrong regarding ideology. There really is not a lot of daylight between the two parties. They both adhere to principles of democratic socialism and their candidates for Knesset are nearly identical when looking at the central policy issues they promote. Making matters more difficult, Labor no longer has a “security expert” in a realistic spot in their list. Omer Bar Lev, currently serving as Minister of Internal Security, was booted down to the ninth spot and is unlikely to return in the next Knesset.

Yesh Atid, headed by Prime Minister of the transition government Yair Lapid, is currently the second largest party in the polls with approximately 24 seats. Lapid is the central candidate on behalf of the anti-Netanyahu camp comprised mostly of center-left and a few center-right parties. Sitting in the Prime Minister’s office, Lapid is in the best position to increase his political clout. He has all of the opportunity to show achievements and to prove himself as a national leader. From the positive outcome of Operation Breaking Dawn in Gaza to preventing a potential nation-wide teachers’ strike on the opening day of school, Lapid has successfully displayed his ability to manage crises within the government and on critical issues of national security. This has allowed to him slowly gain ground in the polls.

Lapid’s most significant challenge will come from the newly formed National Unity Party headed by Minister of Defense Benny Gantz. On July 10, Gantz and Justice Minister Gideon Sa’ar, announced the first merger of the election campaign and formed a joint list that sternly opposes sitting with Netanyahu and seeks to form a “stable and broad unity government.” Not long after, two more important public figures joined their ranks—former IDF Chief of General Staff Gadi Eizenkot and former Religious Affairs Minister Matan Kahana.

Ideologically, there is not a lot in common between these candidates. Gantz hosted Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas in his personal home in Rosh HaAyin this past year, and has spoken of his support for a two-state solution. Eizenkot has also adopted similar positions, publicly expressing his support for reaching a final peace agreement with the Palestinians. In contrast, Sa’ar and Kahana pride themselves on strengthening the Jewish settlement movement in Judea and Samaria.

So, what’s the glue that will make this union last?

Two working mechanisms have allowed for these figures to form a single list. The first is that they all wish to see Netanyahu ousted from politics and oppose forming a government with him. The anti-Netanyahu fever has brought more ideological opposites together in Israeli politics perhaps than any other issue in recent decades.

See related: Just-Bibi / Just-Not-Bibi is Only Half the Story

The second is their adoption of a formula that bridges their ideological divide on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—”Shrinking the Conflict.” Based on the assumption that a permanent solution to the conflict is out of reach in the immediate future—no matter what solution that is—there are immediate steps that can be taken to increase the capacity of self-rule for the Palestinians without harming Israeli security. It is assumed that this will prevent a one-state reality in which the Palestinian Authority collapses and Israel must return to Palestinian cities to directly govern their daily lives in fear that this could lead to eventual annexation. On this point they all agree.

With Gideon Sa’ar and Matan Kahana, the list will be fighting to recruit frustrated right-wing voters who usually vote for parties like Likud, but who wish to see the Netanyahu era come to a close.

Yisrael Beitenu, headed by veteran politician Avigdor Liberman, has remained relatively quiet thus far in the current election season. Ironically, Liberman is one of the original champions of the anti-Netanyahu stance from the political right, especially by someone who was for years seen as a natural political ally of the former premier.

One of his MKs, Eli Avidar, left the party in order to establish a new party called Israel Free. It was a bizarre move that at this point only hurts efforts to form a future government that does not include Netanyahu, since the party is unlikely to pass the electoral threshold in November. Yisrael Beitenu is expected to remain consistent in the polls as it reaches out to its traditional electorate—a mostly Russian-speaking public.

The final list in the anti-Netanyahu camp is the Arab Joint List. A historic split is currently happening within the party. Balad, the more nationalistic faction in the list headed by Sami Abu Shehadeh, not only refuses to support any candidate for Prime Minister, but is pushing a hard line for zero cooperation with the Zionist parties.

In the past, the Joint List has cooperated with the governing coalition in order to promote its own agenda. This way, it could maximize its parliamentary achievements without actually having to become a member of an Israeli government. The other two factions, Ta’al and Hadash, are more pragmatic in their positions and are at odds with Balad. It is likely that each will run as an independent party. This will increase the risk that one of them could fall short of the electoral threshold, and as a result decrease Arab representation in the Knesset.

All of the parties mentioned until this point form the camp that is almost certain (nothing in Israeli politics is absolutely certain) to oppose joining a coalition with Netanyahu.

Now, let’s dive into the pro-Netanyahu right

After Naftali Bennett decided to take a break from politics, Ayelet Shaked was handed the keys to the Yamina party. In her next move, she reformed the party and gave it a new name—The Zionist Spirit. Many of the parties’ former members, such as the aforementioned Matan Kahana, have left its ranks, bringing with them much of its original voters. Moreover, what appeared to be a “failed” tenure in the last government in the eyes of many right-wing voters has severely damaged the party’s image.

In one attempt to overcome this issue, Jonathan Pollard, an American who made Aliyah after he was jailed for decades in the United States after passing on classified intelligence information to the Mossad, published a video expressing his support for Shaked. Pollard said that she “has learned from her mistakes” in the last government. After receiving heavy criticism, Pollard recanted his endorsement and deleted the video from social media. For Shaked, this was a desperate effort with an embarrassing end. Her party is plummeting in the polls and is nowhere near the threshold. She either needs to find an entirely new branding for the party, or merge with a larger existing one.

The Likud finished their primaries recently and, unsurprisingly, the MKs most loyal to Netanyahu did very well. Yariv Levin, Netanyahu’s right-hand man during the last Knesset who spearheaded efforts to break up the government, finished with the most votes. However, the party was heavily criticized since there are hardly any women in realistic spots on the list. There are just two women in the first 20 spots. Netanyahu is now under immense pressure to place women in the reserved spots in the list, which he can choose.

Nevertheless, the Likud has a commanding lead in the polls with around 32 seats. This is unlikely to change between now and November. The Likud needs to make sure that its loyal supporters go out and vote. Because of the abnormal frequency of elections there is less and less motivation to vote in each successive election. The public is tired of the continuation of the political crisis. In the fight to gain a 61-seat majority, every vote counts.

The far-right Religious Zionist Party headed by Betzalel Smotrich is an unquestionable ally of Netanyahu. After intense negotiations mediated by Netanyahu himself, the Religious Zionist Party and the Jewish Power party headed by Itamar Ben Gvir have united into a single list.

When running independently, these parties are unlikely to reach the electoral threshold. In the past, Jewish Power ran on a single ticket unsuccessfully. For Smotrich, this would be his first time running alone. Either of these parties not passing the threshold would be a disaster for the Right in general, and for Netanyahu in particular. It would be virtually impossible to form a government without them.

Agreeing to merge lists with Ben Gvir was not an easy choice for Smotrich. Ben Gvir is perceived as too extreme for many in the religious Zionist public. He was a faithful student of Rabbi Meir Kahana and adopted many of his positions, such as proposing a transfer of Israel’s Arab minority population out of the Jewish state. Moreover, many protests that he’s participated in were accompanied by racist chants like “death to the Arabs.” It’s also hard for many to erase from their minds the fact that for years he praised Baruch Goldstein, a Jewish terrorist from Kiryat Arba who entered the mosque at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron and massacred a score of Muslim worshipers in 1994. Today, Ben Gvir says that he has changed. “I used to say that we need to get rid of all of the Arabs, now I say we need to get rid of the terrorists.” This may convince some, but for many, Ben Gvir is strategically paving his way to become a minister in a Netanyahu-led government.

Either way, the merging of their parties has most likely saved them from electoral elimination. They currently stand at 10 seats in the polls.

The Haredi parties have also had their fair share of struggles with unity. As of now, there is a major split taking place within the Ashkenazi United Torah Judaism Alliance made up by Hasidic and non-Hasidic ultra-Orthodox factions. At the core of the disagreement lies an issue pertaining to integrating state-based curriculae in the Haredi education system.

Recently, the Belz Hasidic sect began incorporating what is referred to as ‘core’ curriculum issued by the Ministry of Education. For some in the Haredi community, this is the only way for its members to integrate into the work force and provide for their families. Without this basic education, graduates of this system possess no practical tools for life outside of Yeshiva. However, there are others that see this is a gateway for leaving the Haredi way of life, therefore threatening the community.

For Netanyahu, this could very well constitute a major obstacle to gaining a majority after the election. Similar to the Religious Zionists, the Haredim are loyal allies to Netanyahu. They know how to work with him and usually receive most of their policy requests. However, they typically do not campaign with independent lists. They too face the risk of not reaching the electoral threshold if they choose to run separately. Netanyahu is unable to form a government without these crucial seats.

Finally, Ra’am, the Arab Islamist party headed by Mansour Abbas, is probably the only party that is at present willing to consider sitting in almost any coalition, even one headed by Netanyahu. Their last stint in the so-called “government of change” earned them plenty of criticism from within the Arab community. But at the same time it also produced a sense of hope that policies for the benefit of Arabs in Israel can be passed through participation in the coalition. Although Ra’am is hovering close to the electoral threshold, it is still expected to pass and return to the Knesset. Ra’am again could be the party that decides this election’s final outcome.

See: “Assyria Sets Up New King Over Israel”

At the end of the day, Israel still finds itself amidst a serious political impasse that produces very little political stability. Even when there is a government it is usually short-lived, and elections are constantly looming.

Nevertheless, I think that we are in a transition period. We are inching our way into a post-Netanyahu era, whether you see that as positive or negative. The ‘change’ government gave the Israeli public a taste of what government is like without Netanyahu. Israelis have now seen that the country will continue to function properly even with Bibi out of power.

Could Netanyahu still become the next Prime Minister? Very much so. However, the more he stays away from the coalition and out of the position of prime minister, the closer he is to the end of his political career and the end of an era for the State of Israel.