(JNS) As millions of Israelis resumed routines and activities interrupted by the war with Iran, life ground to a halt last week in the Druze communities of the Golan Heights.

A massacre perpetrated on July 13, in which hundreds of Druze Syrians were reportedly murdered, has shaken Majdal Shams, a picturesque town that’s home to most of the Golan’s 20,000-odd Druze residents, many of whom have relatives across the border.

“This is our Oct. 7,” Sari Halabi, whose home in Majdal Shams is situated 50 yards from the border fence, told JNS on July 17. “Life froze. We keep watching the videos that the terrorists took of themselves butchering our families, feeling angry, anxious and completely destabilized.”

Alongside the grief and shock that has struck this community, many here feel proud of and grateful for Israel’s robust intervention to stop the massacres—on July 16, the Israel Air Force struck key regime targets in Damascus—and optimistic that the Druze of Syria and Israel would unite in the wake of the massacres.

Following the July 13 massacre in Sweida, a predominantly Druze city in southern Syria, hundreds of Druze living on the Israeli side of the border briefly crossed into Syria without permission out of concern for their families there, as dozens from that country entered Israel to seek safety and see relatives, though most were later returned.

Elsewhere in Israel, Druze citizens, of which Israel has about 150,000, declared a general strike, blocked roads and demonstrated, demanding Israel act to rescue their kin. The protest subsided after Israel struck Damascus on July 16, prompting the Syrian authorities to announce a ceasefire as security forces were deployed to Sweida to end the violent clashes.

Still, the unrest underlined the deep impact that events in Syria have on Israel’s Druze community—a minority that has distinguished itself with loyalty to the Jewish state, including via active and meaningful military service.

Despite the illegal border breach on July 15 and the protests, the Druze attachment to Syria “is an asset to Israel, not a liability,” said Halabi, a 38-year-old father of three. “This attachment opens the path to many things, which I think the terrible massacre has brought closer, including a Druze autonomy fighting and flourishing alongside Israel” on the Syrian side of the border, he said.

Druze residents approach the Israeli-Syrian border fence during a protest rally held in solidarity with their community in Syria, in Majdal Shams, Israel, on July 16, 2025. Photo by Ayal Margolin/Flash90.

This is because “the massacre will help settle an internal debate within the Druze community in Syria, and it will lead to more support for autonomy and self-reliance,” said Halabi. Autonomy, he explained, means deepening the alliance with Israel, which is the only major power interested in a Druze-run buffer entity along its northeastern border.

These geopolitical calculations weren’t Halabi’s first reaction to the massacre.

“I was just sitting there watching the horror videos, one by one. Just like we all did on Oct. 7,” he said, referencing the invasion into Israel by thousands of Hamas-led terrorists, who murdered some 1,200 people and abducted another 251, often while documenting their own war crimes with body cameras and cell phones.

Faced with a stream of images of similar atrocities coming out of Syria, hundreds of Golan Druze gather in the evenings on the eastern edge of Majdal Shams, near Halabi’s home, where Syrian territory is a stone’s throw away. There, they fly Druze flags, share impressions, talk to foreign and local media and survey with their own eyes their communities across the border.

On Thursday, Druze men, some of them wearing balaclavas, ejected Al Jazeera reporters from the town as Israeli troops and police officers guarding the border fence looked on.

“This is not news. This is reconnaissance. They’re collecting information for the enemy,” one young Druze man told JNS of Al Jazeera, the Qatari anti-Israel network.

Security is a concern in Majdal Shams, especially after a Hezbollah rocket killed 12 children at a soccer field here last year. A nearby square commemorates the victims with a statue of a soccer ball adorned with a crown comprising 24 angel wings. Many here say Hezbollah targeted the field and timed the rocket to produce maximum effect.

During last year’s state commemoration of the victims of the war that erupted on Oct. 7, a resident of Majdal Shams, Luna Rabbah, represented the town when she sang a verse in the memorial song “Etzlenu Bagan” (In Our Garden.)

Yad Sarah volunteers pay their respects at the site of the deadly rocket attack in the Druze village of Majdal Shams on July 27, 2024. Credit: Courtesy.

On the border fence, her father, Abdullah, showed the video proudly to a reporter. “The past few terrible days followed a very difficult year,” said Abdullah Rabah. “But it led to an act of brotherly courage that, even though it came too late, will be remembered for generations and saved many lives,” he said of the Israeli strikes in Damascus, including on the Syrian army’s general staff headquarters.

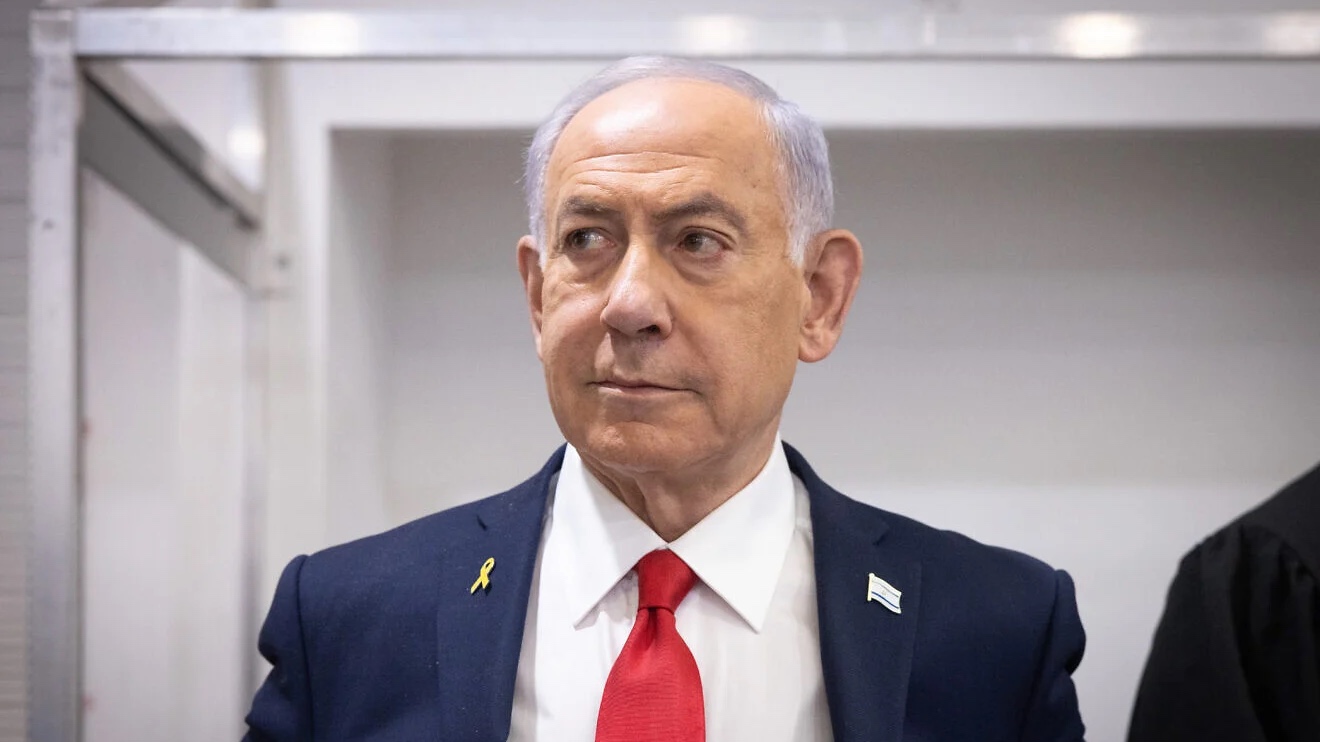

The Syrian regime, led by Ahmed al-Sharaa, a former al-Qaeda jihadist terrorist who rose to power in December, “sent an army south of Damascus, into the area that should be demilitarized, and it began to massacre the Druze. We could not accept this in any way,” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said in a statement on July 17 about the strikes, which Syrian sources said killed dozens of people.

The strikes were out of character for Israel, which very rarely uses military force in defense of non-citizens. Some find the strikes puzzling. “I don’t know what to make of it,” said Ilham, a Druze woman in her fifties who preferred not to give her last name. “Maybe it’s some political plan involving Netanyahu, [US President Donald] Trump, al-Sharaa and the Saudis. I don’t believe it was about the Druze,” she said.

Many Druze in Israel say they feel discriminated against or unheeded, especially following the passing of a law in 2018 that states that Israel is the nation state of the Jewish People, a formulation some Druze argue is discriminatory.

Abdullah Rabah looks into Syria from across its border with Israel in Majdal Shams, Israel, on July 18, 2025. Photo by Canaan Lidor.

Rabah believes that the strikes in Damascus were indeed meant to protect the Druze in Syria, and as such were “an unprecedented act of solidarity that will usher in a new level of integration and fraternity between Jews and Druze.”

Israel’s intervention “will turn a new leaf also for the Golan Druze,” he said, predicting a run on Israeli citizenship.

Most Golan Druze have to date declined citizenship, clinging to an official narrative of being Syrian citizens under occupation while de facto integrating into Israel and plugging enthusiastically into its economy. However, increasing numbers of Golan Druze have taken up Israeli citizenship in recent years as the prospect of being returned to Syria became increasingly unlikely.

“I’m optimistic,” said Rabah, who came to the border wearing a cap emblazoned with the Druze flag on the front and the Israeli one on the back. “Just like Israel emerged from Oct 7. much stronger than it was before, so too will the Druze—and their eternal alliance with Israel,” he added.

Want more news from Israel?

Click Here to sign up for our FREE daily email updates