Hashachar St. is one of the first six streets of Tel Aviv, founded in 1909 with the neighborhood of Achuzat Bayit. It is the name of a Hebrew periodical printed in Vienna from 1868 to 1885. Hashachar (The Dawn) was the project of Russian-born Peretz Smolenskin (1842-1885), a musician and author and the editor of this periodical from beginning to end. It stopped publication with Smolenskin’s death. Hashachar reflected the ideas of the Haskalah movement, which was the Jewish version of the Enlightenment. As such it promoted secular education for Jews, who at that time were confined to the traditional schooling of the Yeshiva.

The ambitious mission statement of Hashachar appeared at the front page of every issue, which said that “HASHACHAR will shed light on the Israelites’ paths past and present.” It then quotes Isaiah 58:8, from which the name of this periodical was taken from: “Then your light will break forth like the dawn, and your healing will quickly appear. ” This verse well reflects the view of the Jewish maskilim (followers of the Haskalah movement) at that time. In their minds Jews were mentally sick people living in the darkness of the ghetto, and the light of the Haskalah was supposed to heal them.

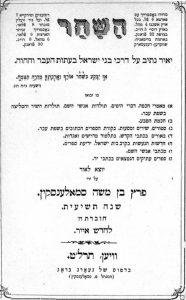

Cover of an issue of Hashacher.

Haskalah, which literally means “education,” was trying to hold the rope at both ends, so to speak. One end of the rope represented the attempt to revive the unique Jewish collective identity, particularly by using the Hebrew language for non-religious purposes. The revival of the Hebrew language started more or less in 1782, when Isaac Eichel founded “The Society of the Seekers of the Hebrew Language.” The result was an unprecedented surge of Hebrew literature, that essentially ended with us Israelis speaking Hebrew. The revival of collective Jewish identity gave birth to the “national sentiment,” out of which came Zionism.

But the other end of the rope represented a desire for the integration of Jews in their respective societies. Integration meant intimate contact with gentiles influenced by the European enlightenment, and opposed any expression of Jewish particularism. This integration caused assimilation in unprecedented numbers, and alienation from Jewish life. These two undesirable results made the ideals of the Haskalah unfavorable, and the movement died out. But the secularization of the Jewish world was irreversible. Zionism, therefore, ended up being a secular national movement, albeit thoroughly Jewish.

Hashachar, which would openly criticize a rabbi for being stagnantly ignorant while welcoming the novel revolutionary ideas of Karl Marx, was a model adopted by many Zionists. Naming a street after Hashachar, therefore, well reflects the sentiment of Tel Aviv’s founders, who wanted to build a modern secular Jewish city that in their minds was true to the vision of Benjamin Ze’ev Herzl, articulated in his book Altneuland, “Tel Aviv” in Hebrew.

Critical as it was of the Jewish world, Hashachar was instrumental in rekindling the love and yearning for the Jewish homeland. In the first issue Smolenskin published his poem, “Love for the Homeland,” that says in a nutshell that, attractive and welcoming as Germany was at that time, Jews there still felt as strangers in foreign land. After praising Germany, the last stanza of this inspirational poem reads:

Ah! If I would dwell in desert, in dry land

And though my homeland is far away from me

And though satiated in foreign land

As long as the land and kingdom of my people lays waste

Even if I dwell in ivory towers sitting on pure gold

I will forget to eat if I forget you Jerusalem.